The period of the Abbasid dynasty, considered the golden age of calligraphy, saw increased diversification and sophistication. It was marked by a breakthrough in the 10th century with the emergence of cursive scripts characterized by smaller, rounder letters, often grouped together, under the name of naskhî.

These new cursive scripts, for practical reasons, took precedence over the kûfî. This radical transformation was essentially due to three great calligraphers: Ibn Muqla (886-940), ibn Bawwâb (d. 1022) of the Baghdad School and al-Musta’simî (1203-1298) who, two centuries later, perfected the theorization and practice of the art of cursive writing which is used to this day.

Although the original aim of calligraphy was to improve writing techniques to make them clearer and more beautiful, it increasingly came to embrace the pre-eminence of plastic form.

During the Abbasid period, the Fatimid caliphate dynasty (909-1171), also known as the Obeydid, extended its reign over the Maghreb, Sicily and parts of the Middle East. This Shi’ite Ismaili dynasty (10th to 12th centuries) was distinguished by the great finesse and sophistication of its calligraphy. Various styles, such as kûfî, thuluth, naskhi and muhaqqaq, were used to create harmonious compositions. Using feather quills, they were able to trace delicate, flowing strokes, mastering the art of composition and balancing letters to produce aesthetically pleasing works. They were also the founders of al-Azhar University in Cairo, in 970 CE.

1. The Baghdad School

The Baghdad School owes its name and reputation to the successive contributions of three eminent master calligraphers. The political, economic and intellectual environment in which they worked was conducive to the blossoming and cross-fertilization of ideas from a variety of disciplines. These masters encouraged and promoted the development of the arts. Following in the footsteps of their predecessors, their research brought improvements and innovations, in a continuity and without pause, each in a specific field. The innovations of Ibn Muqla (886-940) — while resolutely original — in no way contradict the example set by his predecessors. The same is true of the innovations of his successors. This school is an excellent example of the exchange and transmission of knowledge.

Numerous disciples of these three founding masters, including a number of women, bequeathed a rich artistic heritage which has been preserved to this day. Shaykhah Shudah (1091-1178), known as Fakhr-un-Nisa (the pride of women), daughter of the renowned scholar Abu Nasr Ahmad Ibn’ Umar Al-Abri (d.1112), who was also her teacher, excelled in many sciences and was particularly renowned in the art of calligraphy.

Gold coin

Abbasid period

Caliph Abû Jaffar Mansûr

Baghdad, 754-775

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-1667

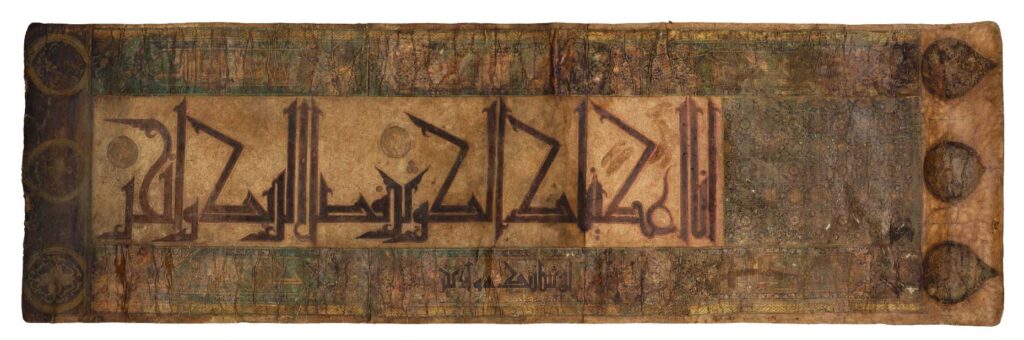

Handwritten scroll

Sura CVIII

Style: Kûfî

Parchment, 133 x 43 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-613

2. Founding masters

2.1 Abû ‘Ali Muhammad Ibn Muqla (886-940)

A poet and writer who served as vizier, he applied the laws of geometry to codify letters and fix their proportions. This system of rules is based on the form of the letter alif, around which a circle is constructed. The alif, whose measure is the diameter of this circle, becomes the standard letter. Each letter is then developed from this circle. In this way, the curvature of the cursive script triumphs over the angular rigor of kûfî. He accomplished a kind of revolution, eliminating the use of the kûfî script and replacing it with the naskhî. Ibn Muqla left an Epistle on writing and the calamus (Risalat al-khatt wa-l-qalam), a copy of which is preserved in Cairo. It discusses techniques and codes, as well as the calamus and its cutting, and ink and its preparation. Abdellah ibn Zandji (10th century) refers to him as a “prophet in the art of calligraphy”, adding that his gift is comparable to the inspiration of bees, who construct the cells of the honeycomb.

2.2 Abû al Hassan Alâ-eddine Ali ibn Hilâl, known as Ibn Bawwâb (961 – 1022)

Also known as Ibn Sitrî, he was an intimate of the vizier Fakhr al-mulk Abû Ghalîb Muhammed b. Khalâf (965-1016). A decorator by trade and a great scholar, he turned to calligraphy and illumination. After bringing together the various forms of writing of ibn Muqla, he refined them by improving the processes until he found his own style. He introduced the measuring-point, obtained by the oblique line (al-khatt) left by the reed on the paper, from which each letter is measured. He perfected and embellished various scripts, especially the naskhi and muhaqqaq styles.

As Curator of the “Buwayhide Bahâ’ al-dawla” library in Shirâz, he was responsible for making copies of many of the books known at the time and sixty-four manuscripts of the Qur’an, one of which was donated to the library of the Lâléli mosque in Istanbul by Sultan Salim Ist (1470-1520). His copy of the “Diwan” by Salama ibn Jandal (d. 639) is in the library of the Aya Sofya (Hagia Sophia) mosque, also in Istanbul. To date, only one copy of the Qur’an has survived from this calligrapher, currently in the Chester Beatty Library (Dublin).

A famous woman from this period also stands out. An expert in the style of Ibn Al-Bawwab, Fatimah Bint al-Aqra’ (d. 1087), is renowned for her teaching of the art of calligraphy. Her work inspired many artists who came to learn from her. She practiced her art in the service of the first Seljuk sultan Tughrul Beg (995-1063) and his vizier, al-Kundari (1024-1064). She was invited by the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadî (1056-1094) to draft the truce agreement between the Abbasids and the Byzantines.

2.3 Jamal Eddine Yâqût Al-Musta’simî (1203-1298)

Jamal Eddine Yâqût Al-Musta’simî was the slave of the thirty-seventh and last Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad, Al-Musta’sim Billâh (1212-1258). From the very start he was a technical innovator, working on the straight-cut calam (jazm), then on the oblique-cut calam (muharraf). His reputation soon grew, and he became the “model for calligraphers” (Qiblatu-l-Kuttâb). He is credited with the ultimate refinement of the art of writing and its final theorization, as well as with the finest manuscripts of the Qur’an preserved to this day. Some claim that he copied the Qur’an a thousand and one times. The Paris National Library owns a copy which is preserved in the Shefer collection (Arabic manuscripts, no. 6082).

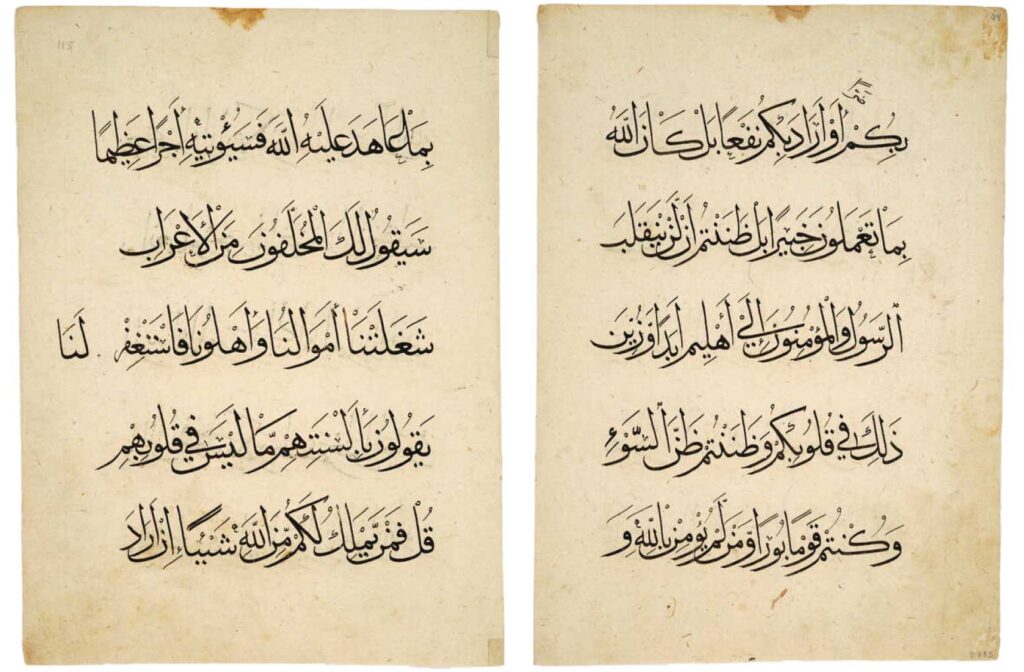

Pages from a Qur’an

Sura XLVIII, 11

Style: Muhaqqaq

Paper

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-603

Terracotta seals with different motifs from the Fatimid period

10th century – Egypt

Diameter: 7 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-377

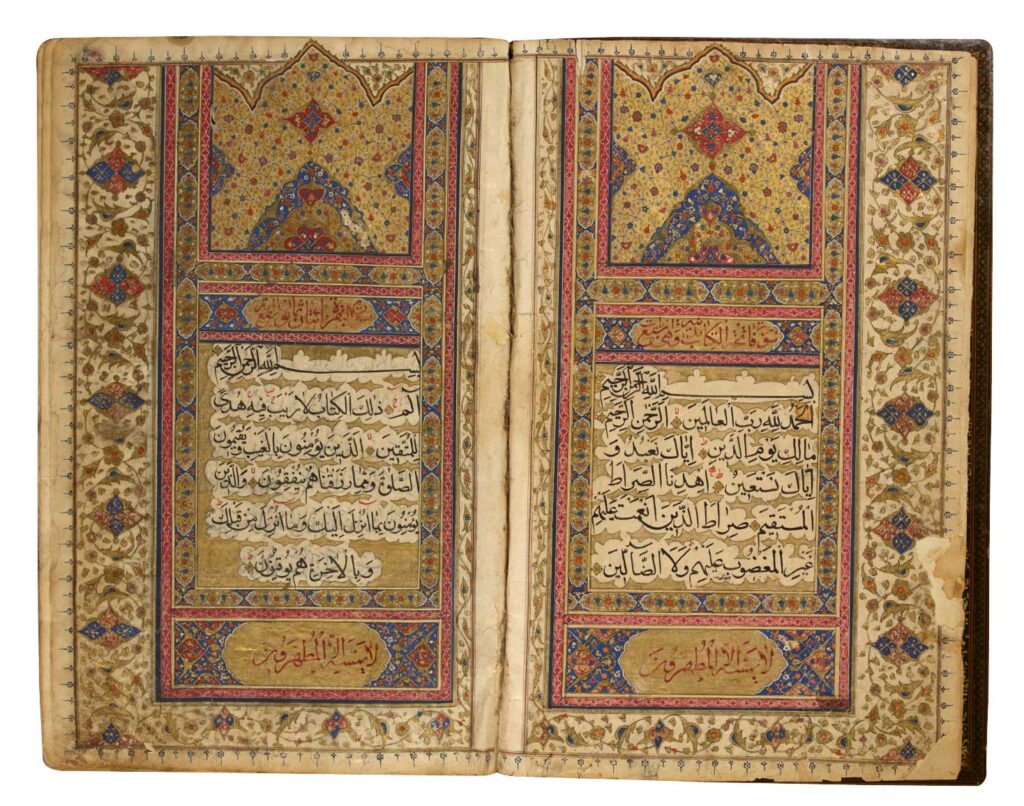

Manuscript of a Qur’an

Sura I and Sura II, 1-4

1771

Copyist : Muhammad Husayn b. Nâsir Ali

Style: Thuluth

Paper, 33 x 22 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-132

3. Calligraphic styles

Naskhî (10th century)

Etymologically, nashkî derives from the verb “nasakha“, meaning “to copy”. Codified in the 10th century, this style was developed by the great calligrapher Ibn Muqla (886-940). It is characterized by its readability, balance and speed of execution. This script, known as “cursive”, features a supple, rounded form. Each letter of the alphabet has its own well-defined aesthetic canons. It rapidly became the most widespread script throughout the Arab-Muslim world.

In the 10th century, paper replaced parchment, enabling the production of more and more books. Other calligraphic styles developed to the detriment of kûfî, previously considered the reference for Qur’anic writing. Nashki spread with the Fatimids around the 12th century and, more particularly, under the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria (1250 to 1517).

Glazed terracotta tile

Seljuk period

22 x 23,3 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3107

Brass pencil box (Qalamdan) inlaid with silver

Style: Thuluth

6 kg, 50 x 13 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-469