For centuries, calligraphers have used a variety of instruments and supports to write and create their works. Pens carved from reed or other precious materials such as bone, silver and gold, were essential for calligraphy. Their precise size and careful preparation were necessary to trace impeccable lines.

1. The instruments

1.1 Calamus (Qalam)

The Arabic word “qalam” corresponds to the Greek word “calamos” or “calamus” in Latin. It refers to a quill pen cut from feather or reed, and has been used for writing since its origins. It comprises three elements: a smooth, shiny outer layer, called the “bone” or “batn al-qalam”; a porous part, called the “fat” or “chahmat al-qalam”, which must be removed; and between the two, a more fibrous layer, the “flesh” or “al-qichra”.

Knowing how to properly trim the calamus is a basic necessity. The width of the beak should be, on average, half the outside diameter. The operation is carried out in four stages: opening, carving, splitting and cutting.

In his work entitled “Al-Fihrist”, Ibn Nadim (936-995) lists several types of feather or reed pens (calamus):

- The reed calamus, called “qalam al-waṣṣāf” or “qalam al-bāmir”. This is the most common and oldest Arabic calamus.

- The black reed calamus, called “qalam al-ḥadīd”.

- The bone calamus, called “qalam al-ḍabīr”.

- The silver calamus, called “qalam al-fidda”.

- The gold calamus, called “qalam al-dhahab”.

- The steel calamus, called “qalam al-hadīd al-aswad”.

- The tin calamus, called “qalam al-falāsifah”.

- The lead calamus, called “qalam al-rammās”.

- The ivory calamus, called “qalam al-fil”.

- The horn calamus, called “qalam al-qarn”.

2. The tools needed

to cut a calamus

2.1 Pocket knife

To carve the beak, you need a knife or penknife with a fine, sharp blade and a bone or ivory carving tool called a “miqat” or “miqatta”.

2.2 Cutter (miqat or miqatta)

This is a cutting plate that supports the “qalam” during cutting. A sort of recessed indentation is fashioned to hold the “qalam” in balance as it splits and cuts the beak. It also serves to catch any excess ink left on the “qalam” when the calligrapher sets it down.

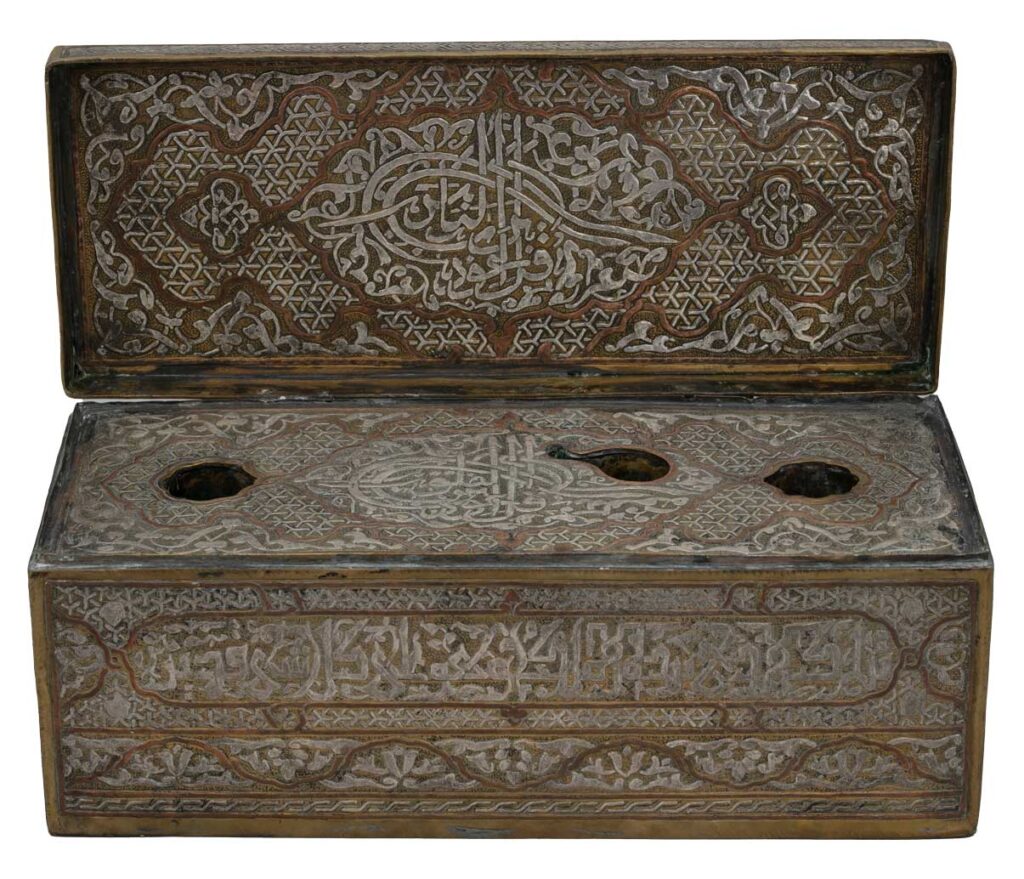

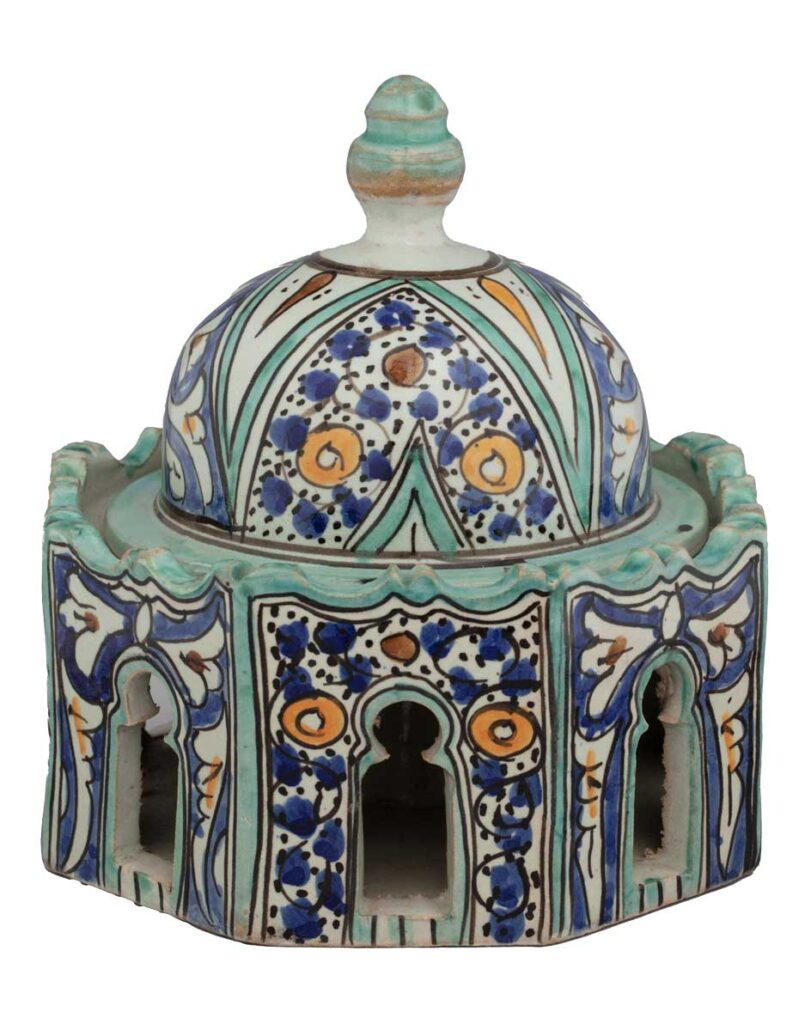

2.3 Inkwell

The inkwell is of great importance to the calligrapher. Some are designed to be used when traveling (portable inkwells). They consist of a small cup with a lid designed to hold dry ink, to which water must be added when required. A long case holds the calamus (quills). It is usually attached to the belt. Each inkwell contains a “liqa” at the bottom. The liqa is a kind of oakum (sponge, cloth) placed at the bottom of the inkwell, sometimes made of silk threads, to prevent damage to the fragile calamus beak, which is filled with just the right amount of ink. It also minimizes damage in the event of the inkwell tipping over.

The oldest inkwells are made of stone. More recent ones are made of porcelain, glazed ceramic, glass, copper or more precious metals such as silver and, exceptionally, gold. They are sometimes decorated with proverbs or are even signed.

2.4 Inks

Calligraphers attach great importance to the ink they use, which is generally black. For them, it is considered to be the very flesh of the letter, essential for bringing the traced lines to life. There are two main types of ink used by calligraphers:

- The first, called midâd, is carbon-based and made from lampblack, gum arabic and water.

- The second, called hibr, is made from gallnuts and iron sulfate or green vitriol.

Calligraphers may also use a third ink, called “mixed”, which is a mixture of gallnuts and lampblack. Other ingredients, varying from recipe to recipe, are added: alum, pomegranate bark, cloves, burnt and ground date pits, curdled milk, saffron, honey, egg white, rosewater, or myrtle. At the end of the preparation, the ink is filtered and sometimes perfumed. The most delicate task is to obtain a homogeneous blend of the various constituents. Ancient texts give advice on this subject. A treatise by Ibn Badis, dating from 1025, lists all the ingredients.

2.5 Pigments

These are the ingredients that give color to the ink. Most black pigments are smoke-based. Other pigments come from a wide variety of sources: charcoal, alum stone, gum arabic, earth, a mixture of walnut stain and pomegranate bark, and Indian ink stone.

- Yellow orpiment, an arsenic sulfide, often replaces gold due to its lower price.

- Ochres are extracted from a ferric rock and are composed of clay colored by an iron hydroxide.

- Blue pigments are much rarer. In the past, azurite and especially lapis lazuli stone (as expensive as gold and used for the first two pages of the Qur’an) were used.

- Pigments of plant origin are also used, but are sensitive to light and sometimes require large quantities: flowers and leaves, saffron, pomegranate skin, walnut bark, or henna leaves.

- Animal pigments such as cochineal are used for red and purple.

2.6 Layering (Qalab)

When a calligrapher builds a complex composition, there is no room for error.

To ensure that each of his letters is in exactly the right place in the composition as he imagined it, he sketches his calligraphy on a sheet of paper and makes the necessary corrections. Then, he takes a very thin gazelle skin or, later, tracing paper and places it over his sketch, piercing the contours with a fine needle to obtain a qalab. Then, using a fine cloth pouch filled with crushed charcoal, he stamps the qalab onto a thin piece of paper. When he gently removes the qalab, the outline of the dotted line of his composition appears. Finally, he uses a qalam to calligraph along the lines left by the powdered charcoal.

2.7 Hannach

The hannach is a reading pointer. It is generally shaped like a long rod. It is made of bone, wood or silver. It is used to memorize the Qur’anic verses that pupils read on the lawha (wooden Qur’anic tablet).

2. Writing supports

2.1 Parchment

The choice of writing material has evolved over the centuries and across cultures. Originally, parchment came from the city of Pergamon (modern-day Turkey). A transparent or opaque material with a smooth surface, suitable for writing, bookbinding and other uses, obtained by drying untanned limed skin from sheep, goats and gazelles, it gradually supplanted papyrus. Its cost and production time made it a rare and precious support material.

2.2 Papyrus

Used in ancient Egypt from the time of the earliest civilizations, papyrus remained one of the main supports for Arabic writing until the arrival of paper (10th century). The Abbasid caliph Al-Musta’sim (796-842) encouraged papyrus production by establishing a papyrus factory in 836. Papyrus was also used in Sicily, Northern Syria and Mesopotamia, from where many papyri written in Arabic during the first four centuries of the Hegira and preserved today originate. The most frequent sources of papyrus were Upper Egypt, Fustat (Cairo), Damascus, Palestine and the Abbasid capital Samarra.

2.3 Paper

The secret of papermaking was passed on to the Arabs by the Chinese in Samarkand in the 8th century. The first Arab paper was made from cotton, silk or hemp. It had to be smooth and slightly absorbent to be suitable for calligraphy. Before use, it was often dyed and treated in various ways, notably with rice starch or alum. The paper is polished to a high gloss using agate, jade or even camel tooth. These treatments are carried out by the calligrapher or a specialized craftsman. The administration adopted it because it was more difficult to falsify than parchment, which could be erased.

The use of paper spread mainly in the 11th and 12th centuries, reaching as far as Andalusia, from where it made its way to Europe. Its lower cost and ease of use were the reasons why it supplanted other materials.

With the advent of paper, the trade in books developed. Composing a manuscript required several experts: the paper cutter (qâti’ al-waraq), the calligrapher (khattat), the copyist (al-nâsikh), the illuminator (muzayyin), and finally the bookbinder (mugharrif).

“A quarter of the art of writing lies in the blackness of the ink, and a quarter in the skill of the scribe; a quarter in the regularity of the size of the calamus, and the last quarter comes from the quality of the paper”. Al-Qalqashandi (d. 1418)

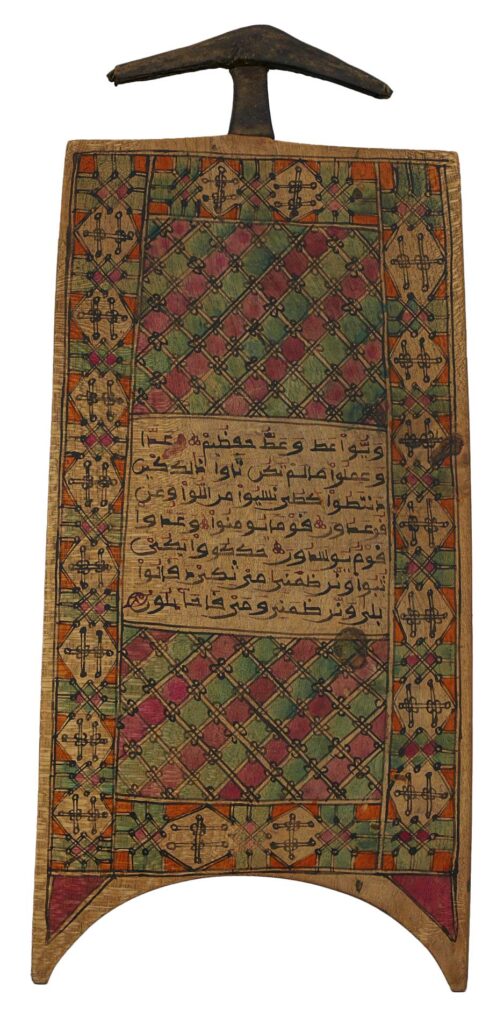

2.4 Qur’anic tablet (Al-lawha)

In traditional Qur’anic schools (kuttâb, m’aamra, djamâ’), children use wooden tablets called “lawhât” (“al-lawha” in the singular) to learn to write, read and memorize the verses and suras of the Qur’an.

Writing on a tablet requires special preparation, which each student must do on a daily basis. Previously memorized verses are erased by rinsing the tablet with water. After rinsing, whitish clay is applied to the still-moist surface, then left to dry so that new verses can be copied with a calamus and “smaq” ink (made from sheep’s wool soot).

Initially a simple study and memorization aid, they become, at certain stages of learning, a kind of diploma of completion (khatma). The tablets are then decorated, often by the master’s hand, and taken home to be treasured as a reminder of the words revealed on the protected “Al-lawh al-mahfûz” or guarded Table, literally unalterable. (Qur’an: 85: V 22).