Predecessors of the Ottoman Empire, the Seljuks (11th-13th centuries) left their artistic and cultural mark on Turkey, Iran and Iraq. Calligraphy of this period preserved classical Arabic styles while developing new forms, including the Seljuk-Thuluth style. Used for monumental inscriptions, it is characterized by its graceful curves and the harmony between thick and thin strokes.

The Seljuks fostered cultural exchange, fusing Persian, Arabic and Turkish calligraphic traditions, and using precious materials to lend a sumptuous lustre to their works.

The Ottoman school flourished throughout the long period of the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the 20th century. It was influenced by earlier styles such as thuluth, naskhî and tâ’lîq, while developing its own distinctive features.

In the Ottoman Empire, calligraphy was widely encouraged and supported by the sultans and the artistic elite. The Ottoman sultans’ courtly patronage produced thousands of Qur’ans and illuminated manuscripts. Istanbul became a center for calligraphic expression, this activity taking over both civil and religious buildings. It reached its apogee during the reign of Sultan Abdelmadjid I (1823-1861), who established the first Academy of Calligraphy to promote the art.

1. Calligraphic styles

1.1 Ruq’â (15th century)

The ruq’â (or “small leaf”) script acquired a popularity that is still undisputed today. This is a typically Ottoman script, which spread with Turkish domination from the 15th century. The letters of ruq’â are short and closely-assembled, set apart from the straight lines in a slightly dotted horizontal pattern, and are written out linked together.

It’s a sober, stocky style, used in everyday writing or common missives, hence its name. It is characterized by integrity and beauty, ease of writing and reading, and simplicity.

1.2 Diwânî (15th century)

Diwânî is one of the most elegant and artistic styles of Arabic calligraphy. Its name derives from the Persian word diwân, meaning administration and, by extension, “imperial council”. It also refers to a collection of poetry in the Sufi tradition. It appeared in the 15th century during the Ottoman period and was codified at the same time by Ibrahim Munîf (15th century). The guiding principle behind its creation was to prevent any alteration of the text, thus differentiating it from religious or scientific writing. It is par excellence, the art of chancery and officialdom.

The diwânî style is distinguished by the large loops that accumulate beneath the lines, and by its slightly accentuated stems, giving it an air of grandeur and majesty. Highly structured and totally cursive in nature, it is devoid of dots and vowel signs, thus offering its calligrapher another mode of expression, “diwâni-jali”, for purely decorative purposes.

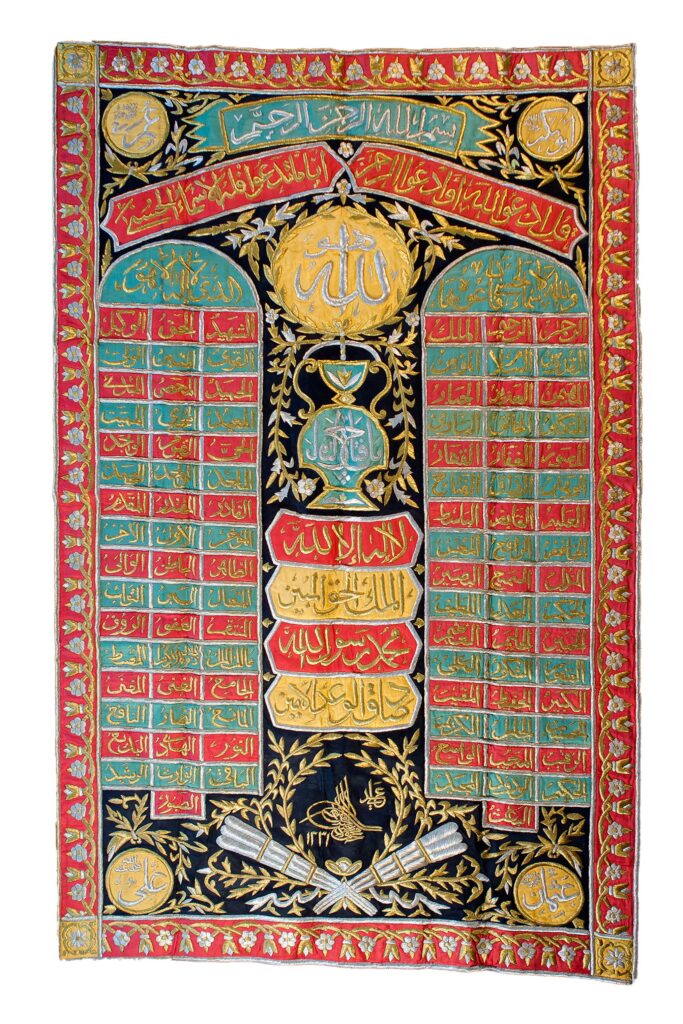

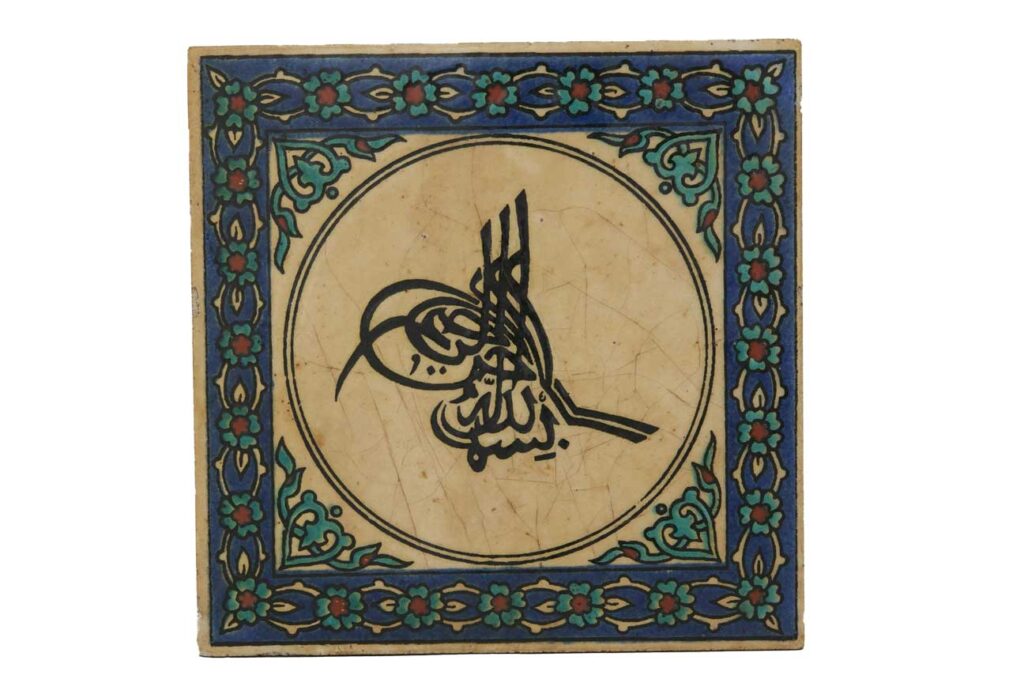

1.3 Tughra: the signature

Tughra is a Turkish word for the calligraphic monogram of the Ottoman sultans. It is a work in itself in certain styles of writing. Its composition contains information including the name of the sovereign. It can also be used as a talisman, with calligraphy of Qur’anic verses and formulas. It reached its classic form under Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566) and became a calligraphic exercise in its own right in the Ottoman Empire.

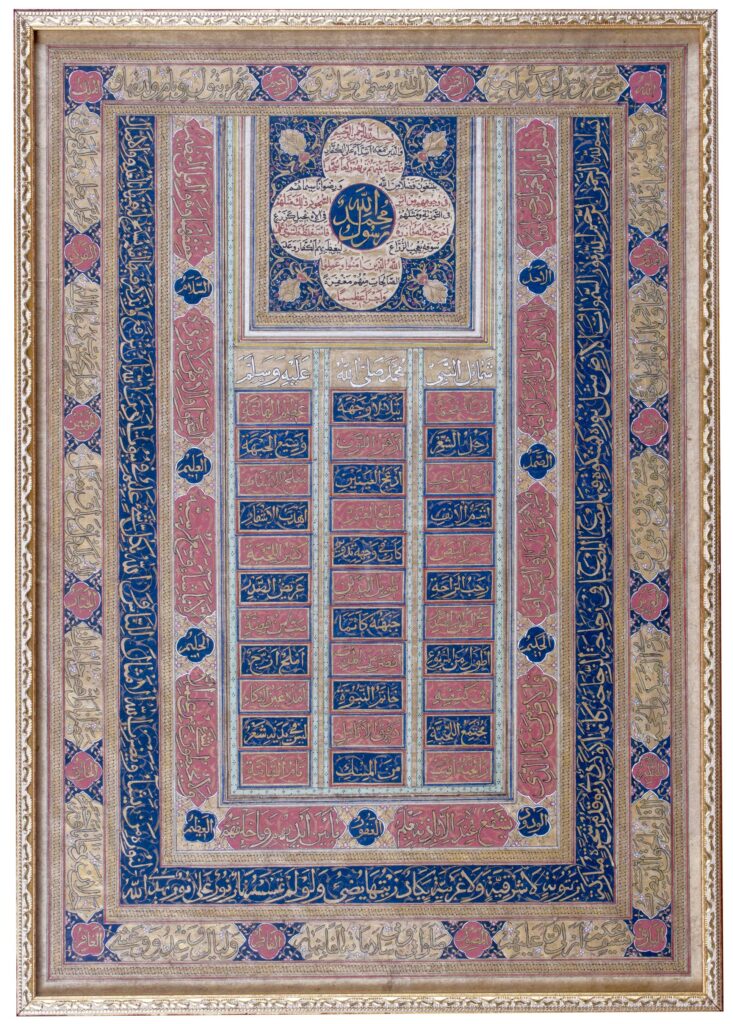

1.5 Hilya

While Sunni tradition forbade any physical representation of the Prophet Muhammad, believers were free to imagine him mentally, based on the description given by Imam Ali Ibn Abî Tâleb, his nephew and son-in-law. It gave rise to the hilya, a calligraphic ornament expressing their love and respect for the Prophet. Throughout history, this practice gained in popularity, particularly in the Ottoman Empire and the Maghreb. Calligraphers created different versions, mixing Qur’anic verses, poems and symbols, making the hilya a precious artistic expression of veneration for the Prophet.

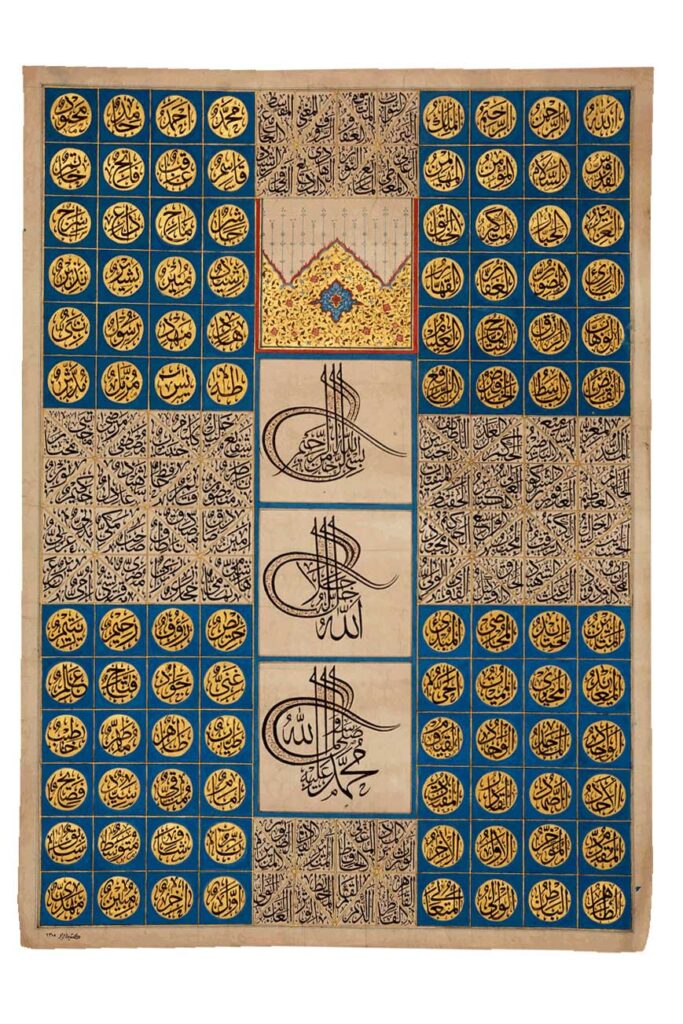

Calligraphy of the divine attributes and names of the Prophet

1890

Copyist: Zubayr

Styles: Thuluth and Tughra

Paper, 83,8 x 61 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-457

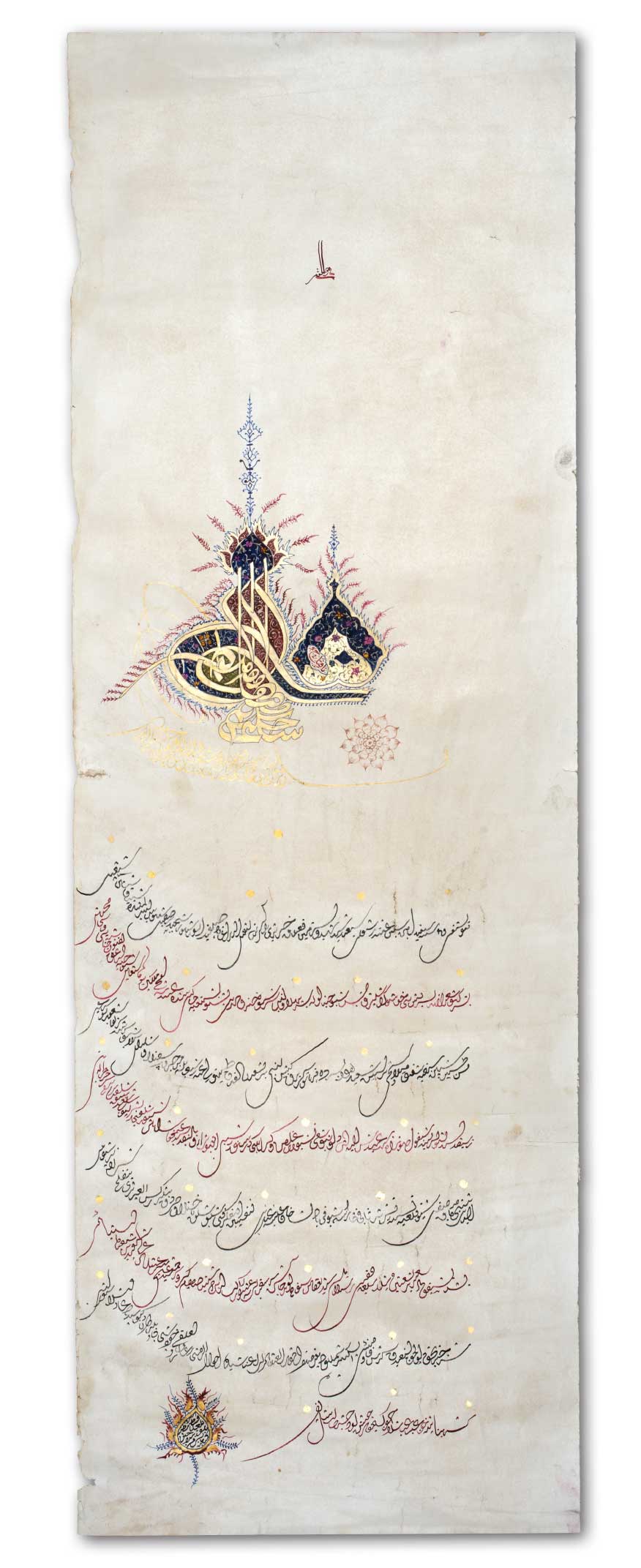

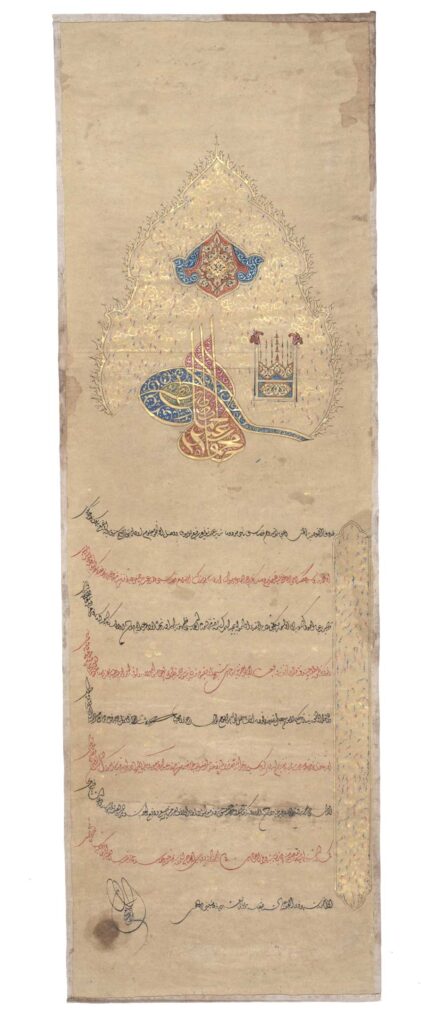

Ottoman Firman (Sovereign Decree) with illuminated signature

Style: Diwânî and Tughra

Paper, 75,5 x 25,5 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-417

2. Founding masters

2.1 Sheikh Hamdullah Chelebî (1436-1520)

He was an eminent calligrapher and one of the founders of the Ottoman school. A native of Amasya, Turkey, he studied with renowned calligraphy masters of his time, enabling him to master various calligraphic styles such as thuluth, naskhî and tâ’lîq.

Admired by many calligraphers, Sheikh Hamdullah was a source of influence and respect for them. As tutor to Sultan Bayezid II (1447-1512), he was appointed head of the Dervish darga (Sufi sanctuary, equivalent to a zaouïa in the Maghreb). This proximity to his sovereign enabled him not only to perfect his style, but also to find ways of passing on the teachings of the famous calligrapher Yâqût al Musta’simî (1203-1298).

2.2 Fatima al-‘Ânî (16th century)

Nicknamed “the female copyist”, Fatima al-‘Ânî remains a mysterious figure in calligraphy. Although little information is available about her, it is assumed that she followed the teachings of Sheikh Hamdullah (1436-1520). Her calligraphy is elegant and her taste unquestionable. As a poetess, she also composed graceful verses.

Following in the footsteps of her illustrious predecessors in the art of calligraphy, Fatima al-‘Ânî devoted herself to the contemplation of writing, constantly searching for the next book to bring to life. She is one of those women artists who handled calligraphy with grace.

Rose water sprinkler

23 x 9 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3063