The Mamluk sultans were fervent patrons of calligraphers, including Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Zaftâwî (1349-1403) and Zayn al-dîn Abd al-Rahmân b. Yûsuf known as Ibn Sâ’igh (1367-1441). During the reign of this empire, one of the greatest known Mamluk Qur’ans was calligraphed in just under sixty days, demonstrating the virtuosity of the artists of the period.

The Mamluk school reached its apogee from 1230 onwards, distinguished by its use of angular forms, thick lines and elaborate geometric decorations. Calligraphers of the period developed and perfected different styles of writing, adapting them to their aesthetic preferences and the needs of Mamluk patrons.

1. Calligraphic styles

1.1 Thuluth (9th century)

Thuluth, literally meaning “a third”, is the most complex style of Arabic calligraphy. It first appeared in the 9th century and reached its peak of development in the 13th and 14th centuries. Considered a benchmark for assessing the beauty of other styles, it was mainly used by the Mamluks (14th and 15th centuries).

Thuluth is characterized by rounded shapes and a smooth, rhythmic movement, ideal for page headings. The letters are written in two-thirds or one-third scale in relation to the original letter. It is frequently found in mosques and caravanserais, as well as on tombstones, madrasa inscriptions and ornamental plaques.

It was particularly encouraged by the Mamluk Sultan Rukn-Ad-Dine Baybars 1st (1260 – 1277) for decoration on glass, various metals, ivory, textiles, wood engraving and stone carving.

1.2 Muhaqqaq (10th century)

Muhaqqaq is one of the main calligraphic styles of Arabic script. The term muhaqqaq means “ornate” or “embellished”, reflecting the aesthetic characteristics of this style. It emerged in Iraq and Egypt in the 10th century. This majestic style is widely used for copying the Qur’an and other religious texts. It reached its apogee during the Mamluk period in Egypt and Syria (13th-15th centuries).

Muhaqqaq is characterized by great meticulousness, and for decades was considered the benchmark for religious transcription. It is distinguished by its elegant, curved lines and the use of large white spaces between letters and words. Particular attention is paid to letter proportions and regular spacing, creating visual harmony and aesthetic balance.

1.3 Ghubârî (9th century)

Ghubârî script, also known as “dust” script, was originally designed for ultra-confidential missions and the transmission of postal messages by carrier pigeon. Its reduced format later gave rise to miniature Qur’ans, no more than five centimetres high. It is characterized by its small size and is often associated with the naskhî and ruq’â styles.

Historically, Ghubârî script was used to copy short Qur’anic verses renowned for their protective power, such as the Throne verse of Sura al-Baqâra (II, 255). It is mainly found on octagonal miniature Qur’an manuscripts, scrolls and talismanic writings.

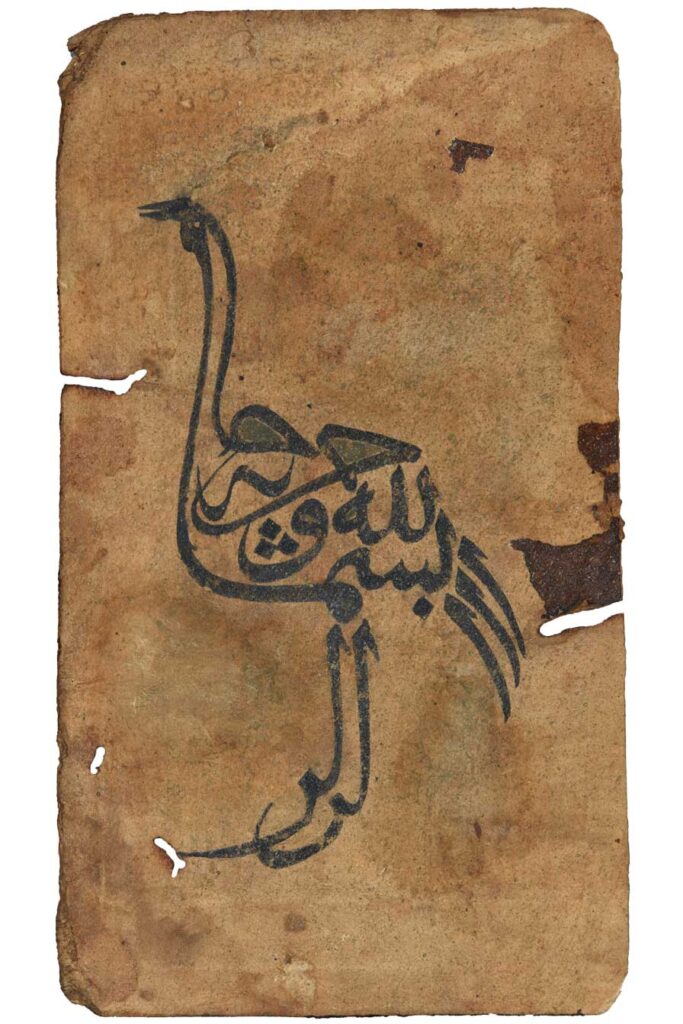

1.4 Zoomorphic style

Zoomorphism, or the use of animals in Arabic calligraphy, has a long history throughout the various cultures of Islamic civilization. Calligraphers developed techniques to give Arabic letters animal shapes such as birds, fish, lions and horses. Over the centuries, this practice evolved to reflect the artistic and cultural influences of different geographical areas. Arabic calligraphy, deeply rooted in Islamic culture, has thus incorporated various artistic and stylistic elements over time.

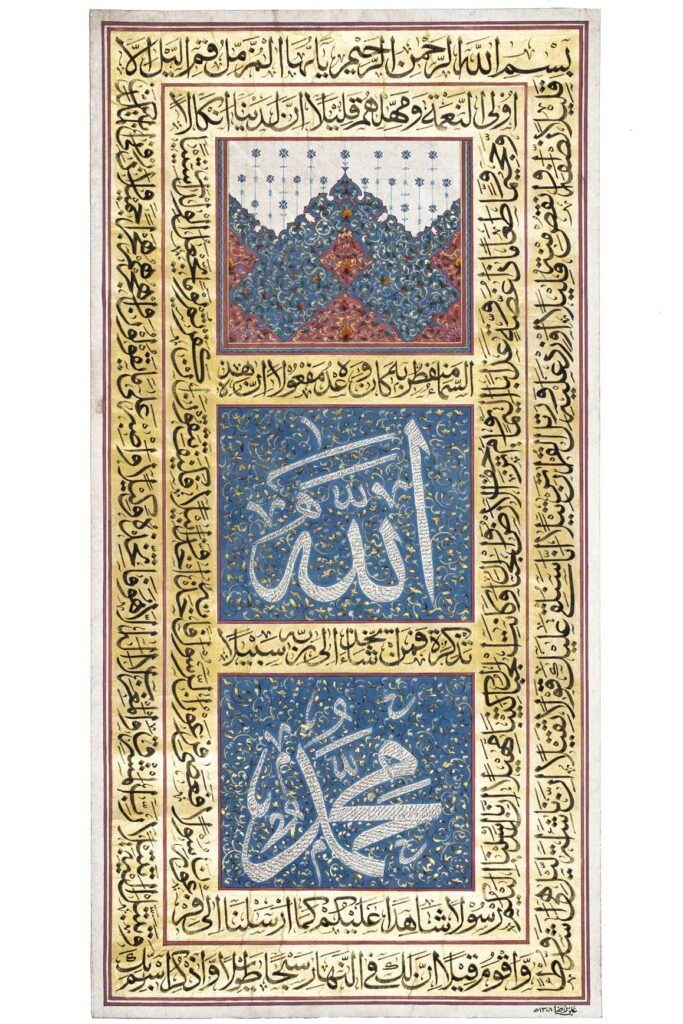

Calligraphy of the name of Allah and the name of the Prophet Muhammad

1890

Copyist: Ali Redha

Style: Thuluth

Paper, 37,5 x 73,8 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-449

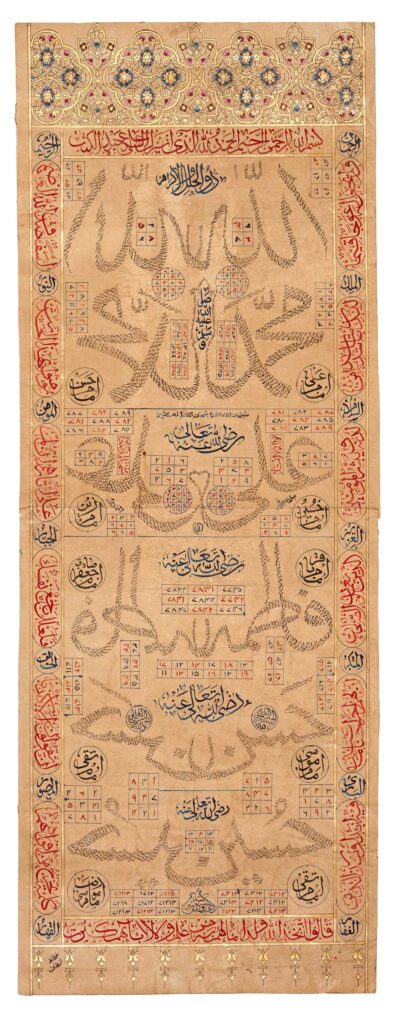

Calligraphies of Allah, Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hassan and Hossein

Copyist: Khattat al-Tâf

Style: Ghubârî

Paper, 29,2 x 78,5 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-448

Qur’an on decagonal leaf

Style: Ghubârî

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-633

2.1 Zayn al-dîn Abd al-Rahmân b. Yûsuf (1367-1442)

Known as Ibn Sâ’igh, Zayn al-dîn Abd al-Rahmân b. Yûsuf was a scribe (kâtib) for the Circassian Mamluk sultan Farâj b. Barqûq (1386-1411). Among his notable achievements are several Qur’ans, one of which stands out for its imposing size, measuring one meter by fifty centimeters. He is also credited with the creation of Qur’anic inscriptions, including the text of Sura al-Fath (Koran: XLVIII), which was carefully engraved inside the Prophet’s mosque in Medina. However, his most remarkable contribution is the introduction of ijâza into the domain of calligraphy.

Islamic vase made of glass with calligraphic inscriptions

Style: Thuluth

19th century

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3124

Zoomorphic calligraphy (bird)

Paper, 19 x 10,5 cm

ADLANIA Foundation, Manuscripts, MAN-519

Engraved wooden bowl (Chifa’)

Sura CVIII

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3129

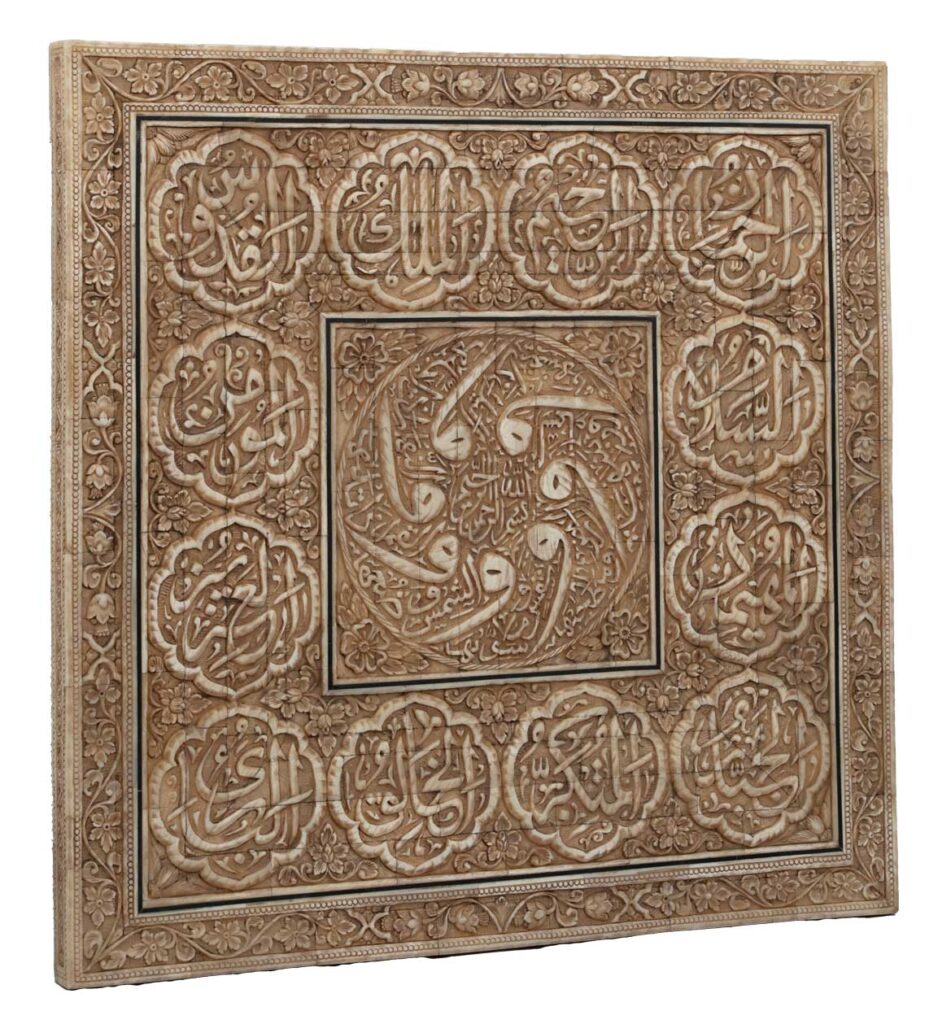

Bone plaque with central medallion

surrounded by divine names

Style: Thuluth

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3100

Hexagonal box made of bone

Floral and geometric decoration with central calligraphy of Sura CVIII

Style: Thuluth

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-3106

Qur’an copied on palm leaf support

Written with a graver (minqâch)

Sura XIX ; 40 verses from Sura XX

Style: Naskhî

Java – Indonesia

ADLANIA Foundation, Objects, OBJ-34