The concept of tradition is fundamentally linked to the transmission of knowledge and innovation across generations. Far from being static, it is perpetuated by new contributions, as seen in the art of calligraphy, which continually combines tradition with modernity.

This practice also illustrates the ethics of calligraphy, known as adâb al-khatt, which links artistic expression to spirituality, highlighting the spiritual geometry that lies in the practice of forming and linking letters and words. This art is learned primarily through the close relationship between master and disciple, emphasizing the essential role of listening, observation and the acquisition of meaningful knowledge. It is the master’s reward for passing on knowledge.

The apprenticeship culminates in the ijâza, a diploma testifying to the student’s mastery of the art. This symbolic passage is accompanied by the production of a specific piece, confirming the student’s ability to create his or her own works. Ijâza spiritually unites master and pupil, underlining the importance of lineage in the transmission of this art. This symbolic relationship recalls the perpetual evolution of tradition, underlining its crucial role as a cultural and spiritual heritage tracing back to emblematic figures of the past, all the while looking to the future.

1. The origins of tradition

At first glance, the notion of tradition suggests the opposite of novelty. Yet the etymology of the word attests to its Latin origin “traditio”, from which derives the verb “tradere” (“trans-dare”), meaning to pass on to another, to deliver, to hand over. In this sense, tradition refers to a succession of innovations that have been deposited, stratum after stratum.

2. The ethics of calligraphy

2.1 Adâb al-Khatt

“Adâb” is a form of conduct that links the material world to the spiritual, horizontality to verticality. It implies an inner and outer attitude coupled with a general culture founded on universal values and belles-lettres.

“Al-Khatt“ meaning the line, expresses the notion of the art of the line. It results from the movement or action of the hand, which starts from the point and draws a line that constitutes the body of the letter. The isolated letter is just an incomprehensible “sound”. It is by linking letters together that we give meaning to a word.

2.2 Transmission of tradition

If a tradition were to remain as it was received, it would become mere conservation, and could even disappear if not revitalized. It becomes a “living tradition” when the received knowledge is replenished by new contributions. It is thus fundamentally linked to the transmission of knowledge across generations, and is perpetuated by new contributions, as exemplified by the art of calligraphy. This practice illustrates the ethics of calligraphy, known as adâb al-khatt which links artistic expression to spirituality, highlighting the “spiritual geometry” that lies in the action of forming and linking letters and words. This art is learned primarily through the close relationship between master and disciple, emphasizing the essential role of listening, observation and the acquisition of meaningful knowledge. It is the master’s reward for passing on knowledge.

This transfer of knowledge is ensured by teachers called “sheikhs” or “mouaddibs” who instruct and educate according to standards inherited from tradition. In calligraphy, transmission requires active reciprocity in the relationship between disciple and master. The student learns not only through words, but also by scrupulously observing the master’s gestures, postures and actions. The latter adapts his teaching according to the progress of his pupil, whose abilities and gifts he perceives. “ In addition to this tension between exacting standards and rigor, energy and emotion play an important role in perfecting understanding and interpretation,” explains calligrapher Ghani Alany.

As musicologist Jean During points out in his book Musique et Extase, l’audition mystique dans la tradition soufie (Music and ecstasy: mystical hearing in Sufi tradition), there is a certain similarity between the calligrapher’s work and that of the musician, who needs to know the solfeggio and the score in order to offer his interpretation: “Underneath the curves of the calligraphy we can make out the framework, just as underneath the so-called ‘free’ melodies (âzâd) we perceive a rhythm, a flow, a breath. The singer breathes to the rhythm of the verse, just as the calligrapher holds and releases his breath to the rhythm of the stroke. The calamus itself is not without analogy with the tip of the fingernail or the plectrum striking the strings of the sitar, the lute or the târ. ».

2.3 The path to ijâza

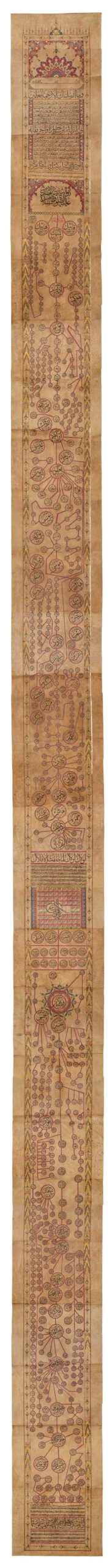

The apprenticeship culminates in the ijâzaa diploma testifying to the student’s mastery of the art. The term means “passage”, “authorization”. This symbolic admission is accompanied by the production of a specific piece, confirming the student’s ability to create his or her own works. Theijâza spiritually unites master and pupil, underlining the importance of lineage in the transmission of this art. In practice, the disciple creates a work composed as follows: After the Basmallâh (In the name of God), he calligraphs a text in a script of his choice, followed by another in thuluththen concludes with a hadith (Saying of the Prophet Muhammad), most often calligraphednaskhi. The master’s approval completes this diploma, which states that the student has reached the degree that allows him to sign his own works. In this way, the student who becomes mujâz becomes part of a chain, forming a new link.

This relationship is a reminder of the perpetual evolution of tradition, underlining its crucial role as a cultural and spiritual heritage tracing back to emblematic figures of the past, while projecting itself into the future, from Hassan al-Basrî (642-728), pupil of Alî ibn Abî Talib (circa 600- 661), and continuing to this day through constant evolution.